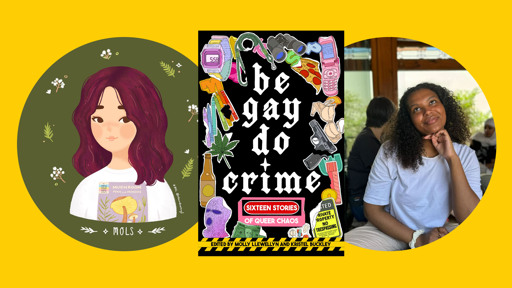

The phrase “Be Gay, Do Crime” is such a current mood that there are actually two books with that title coming out this year. One of these, published by PM Press, is Be Gay, Do Crime: Everyday Acts of Queer Resistance and Rebellion. It offers a historical and sociological overview of queer rebellion and uprising, from the life and work of anarchist revolutionary Emma Goldman to Stonewall to the first Toronto Trans March in 2009, and beyond. Meanwhile, Molly Llewellyn and Kristel Buckley’s anthology, Be Gay, Do Crime: Sixteen Stories of Queer Chaos, is a collection of fiction rather than a historical summing up, and is more concerned with individual acts of gay transgression than with political disobedience and resistance.

Though political disobedience is not the focus of most of these stories of queer criminality, the material conditions that lead to political dissent are present across many of these tales. The characters in these pieces are often living in subpar housing situations, feeling stressed and anxious about crumbling buildings and neglectful landlords, fighting with their roommates and partners in cramped quarters, and weathering the constraints of lockdowns and economic crises. They work dead-end jobs and despair at saving up enough money to access gender-affirming surgeries or start families or make down payments on houses. They bear the rejection of queerphobic and transphobic families and covet the seemingly easy lives of richer, more normative people than themselves. They grit their teeth through racism, institutional and interpersonal, and long for “fuck you money”—a term used in ekwuyasi’s story of the same name to describe an amount of funds impressive enough that it will shut up the racists and haters around you.

The stories in Be Gay, Do Crime bring us from London to Los Angeles; Vancouver to Washington, D.C.; Miami to the Arizona desert. The crimes chronicled in these pages include the mild (weed-dealing, pickpocketing, shoplifting, voyeurism), the more serious (blackmail, stealing a dog, stealing a baby, bank robbery, political assassination) and the zany (impersonating a child in order to win children’s drawing contests, pelting MAGA protestors with rotten beer hops, stealing a billionaire’s experimental anti-dysphoria drug). In Blackburn’s masterful piece of microfiction, “Black Jesus,” the main character’s transgression is spiritual rather than material. A young girl uses Wite-Out to erase the ten commandments in her grandmother’s Bible in order to write in her own, which are more relevant to her life, such as “Thou shalt not drip milk on the carpet.”

The crimes featured in these stories are often born of frustration or resentment, and don’t, with some exceptions, actively harm other people. We aren’t in the realms of Dennis Cooper or Gary Indiana here—there are no snuff films featuring underage characters (real or imagined) or gay serial killers within these pages, or even much that could be deemed smutty. However, many of the characters in Be Gay, Do Crime do get horny when they transgress, with crime becoming an erotic act in and of itself.[…]